As a product leader it is my job to inspire and set the context for the product teams. Here I describe what I mean by setting context, why it is necessary and how I do it.

Innovation

Building products is hard. It requires a good understanding of the job the user is trying to accomplish. It requires creative solutions to solve for the job. It requires excellent execution on these solution.

Let’s – for once – dive deeper on the part that most people think is the magical sauce: creative solutions. Also known as ideas. (Spoiler: It’s not the magic. The process and speed of qualifying ideas is what separates the best from the rest)

So… How do we actually come up with creative ideas?

This is a question older than product management and still not fully understood. Something we do know is that the recombination of other ideas is one way to generate new ideas – similar to the recombination of genes that creates new traits. James Altucher calls this idea sex. Andrew Hargadon argues that most ideas are not even new, but rather the same old concepts re-applied to a new context. Even good old Plato in his theory of ideas states that ideas are the “non-physical essences of all things, of which objects and matter in the physical world are merely imitations.” Kind of like saying real ideas are interfaces and our ideas are the concrete implementations of one or many interfaces (you also read about how software works, right?).

These hypotheses of recombination and re-application are even backed by neuroscience; A study published in 2003 claims that “creative innovation might require co-activation and communication between regions of the brain that ordinarily are not strongly connected.”

Okay, so after some biology, philosophy, engineering and neuroscience we understand that we need a large pool of old ideas we can re-use or re-combine. You knew that.

Who has these old ideas? Everybody!

The more diverse the group’s backgrounds and experiences, the broader the exposure to other ideas as a whole. The more and broader the set of old ideas the group has available, the more new combinations are possible. Let’s call the sum of possible idea-combination the “idea potential” of the group.

Now let’s take a handful of people. Each person is exposed to hundreds or even thousands of ideas through a massive stream of data entering our brain daily. Vaguely remembering what we learnt about combinatorics at school, this results in a sheer infinite amount of new recombined ideas. The idea potential is probably infinitely large as new recombinations (ideas) become available for further recombination.

We have a massive library of ideas to draw on and use to find new solutions with. We won’t run out of new solutions anytime soon. However, how do we tap into this vast depot of ideas without being overwhelmed? How do we surface the combinations useful to us? Enter constraints.

Constraints provide focus and direction. They force tough prioritization decisions and push the team to be entrepreneurial — to use whatever is available to them to get the job done as best they can.

Jeff Gothelf

Innovation can’t happen in a vacuum. It doesn’t. It always happens in context of something. Even if that context is undefined, the mind will create the missing context. Unfortunately each person’s mind will create that context separately. The chances of this being the same context for everybody in the group are very low. We need to create a shared context to make aligned decisions without the need for constant synchronisation.

Constraints are the tool of choice to create the shared context. Additionally they also provide a filter for the ideas that come up in the shared context. The constraints offer a set of characteristics that an idea or opportunity must have to be considered.

Narrowing down the things we are interested in liberates the mind and team. They do not need to care about all the other ideas outside of the context. Nor do they need to ponder the ideas that don’t match the desired characteristics. We reduce the solution space from infinite to defined. A defined space can be explored through scientific rigour and learning – by product discovery.

So how do we set context for product teams?

3P of shared context

The context product teams need is on several time-scales; long-term, mid-term, short-term. Accordingly the 3P’s are: Perspective, Plan and Priorities. The first acts as a compass, the mid-term is the map, the short-term provides guidance on the next steps. All this is pretty hard work and it takes time to create (sorry – no silver bullets here).

Perspective

Perspective is the big what with a 3-8 year outlook (“long” term is industry specific, I am referring to software here). It is derived from the big why – the company’s vision/mission. Perspective offers an ambition, a world-view. Perspective is an opinion, backed with insights. It’s the company’s unique angle of achieving (a part of) the company’s vision with its product. It is tangible, but not descriptive. It is concrete, but flexible. It is inspiring. If anything, it must be inspiring!

Here is some prep-work I do to arrive at a Perspective:

- Thoroughly understand the user’s job we are solving within the context that it happens (ask “when do you encounter <problem>?”). Talk to users (duh), PMs, designers, researchers, sales people, support staff – talk to anyone who can add colour to the picture. Ideally come up with a concept map, pattern language or other form of abstract way to think about the space.

- Understand the possible futures by looking at trends in the market, society, and technology. Are there large shifts that could bring on a change in market dynamics? Which waves can we ride to gain an advantage, which ones do we have confidence in? Do we have a unique insight we can leverage?

- Understand relative positioning to your competition (in the broadest sense possible – “your appointment scheduling solution is competing with telephone calls!”). This means that you first need an overview of the competitive landscape, and a feeling of the trajectory everyone is on. This allows you to think about differentiation.

Now here comes the part that’s more art than science: you need to tell a story. A tale of the user, their struggles, the white knight (your product) that comes to save the day, and all embedded in a future scenario that you are uniquely positioned to capitalise on. The story needs some sprinkles of the evidence you gathered to be believable, but it’s not a scientific paper. It will probably take a few iterations before you nail it. You’ll need feedback and help crafting this.

Here are a few things that helped me:

- Think of giving a presentation to the board, at the company all-hands or a team meeting. You are trying to get morale up, inspire people and rally them around the problem. Envisioning the emotions, reactions, looks on people’s faces helps you craft your story.

- Think about selling to an amazing person you want to hire onto your team. They have offers from the best companies in the world. Why should they join you instead? What mission could they join? How do you make them want to be part of the journey?

- Self-test: Does the story get you excited to work on this problem for the next few years?

- Start. Don’t over-engineer it. Start with something. Get feedback and improve it.

Plan

The Plan answers the questions “where we play” and “how we win”. It details the challenges in the market, how we are different to competitors and how we want to bring the Perspective to life in the upcoming 1-3 years. The Plan is a decision framework for the portfolio of bets, the investments we want to make. The Plan provides guidance to select the strategic mix of bets we want to take (features, growth, expansion, scaling) we’ll talk about in Priorities. The Plan is not a list of things, it’s a model, a set of guard rails, a map.

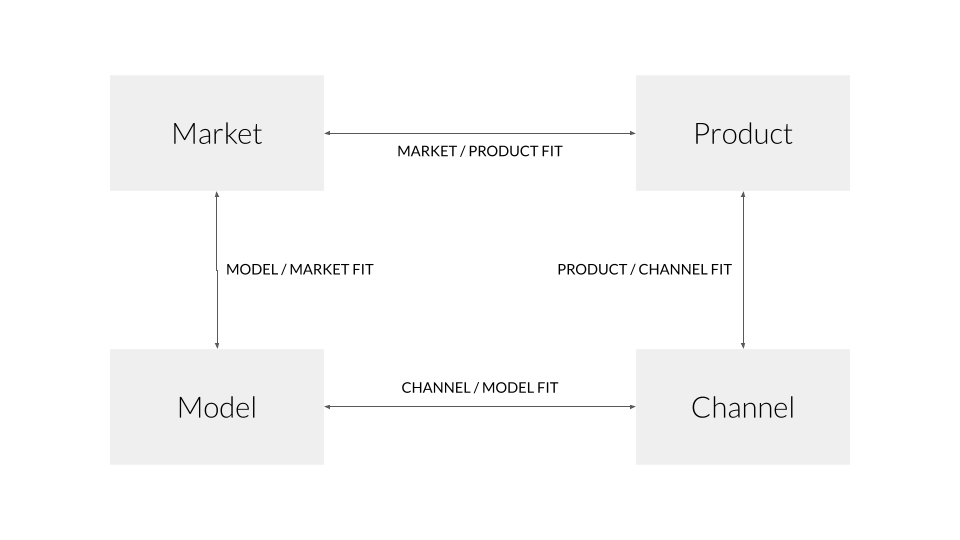

This is where I like to use Brian Balfour’s four fits to clarify my thinking of how the business works.

You can’t think about the fits in isolation. They are connected. They influence each other. Let’s start top left and move around the fits clockwise.

Given the Perspective, we already should have a pretty good understanding of the playing field a.k.a. the market. Nevertheless, we should be more explicit about it for the Plan. Write it down:

- Whom are we building for? (user/customer)

- In which space? (category, industry, geography)

- What problem do they have? (overall job-to-be-done)

- Why is that problem relevant to them? (motivation, why)

From here we can formulate product hypotheses that serve the market (similar to solution hypotheses a.k.a. features to user-problems). If you are working on a product that already has product/market fit (“PMF”), this should just be an exercise in writing it down. If you do not have product/market fit yet, this will be your life for a while: writing product hypotheses and testing them against the market. Don’t try to do anything else yet. Finding PMF is your Plan for now. In both cases you’ll end up answering these questions:

- How is the user’s life better with your product? (core value prop)

- When? (trigger in the user’s context)

- How fast can we get the user to experience the value? What are the steps? (time to value)

- How do we keep the user? How do we build habit? (stickiness)

Once we have a viable solution, we need to think about the channels we are building for. Yes, you read that right: “Products Are Built To Fit Channels, Not The Other Way Around“. Maybe you are betting on an entirely new channel (e.g. AR/VR, in-car) as part of your Perspective or maybe your users are best reached via an established channel (social, search, mobile, ads). Whatever it is, the earlier you know which channel works, the better. Your product needs to be built to power the growth engine. For example, if you rely on SEO and user-generated content, your product should make sure the content generated is heavily optimised for crawlers and checks all the boxes. It sounds obvious, but the difference between a product optimised for a channel and one where it is an afterthought is a major factor in success.

To complete the four fits, we need to decide on a model. This is a whole book in itself, so I won’t go into details here. I might write about it on another occasion. Main take-away is that not all business models work for all markets, channels and products. Business model innovation – usually in combination with a technological innovation – can cause disruption of whole industries. That said, you should obviously be aware of your model.

Now that we know that, we have one more questions to answer: How are we going to compete?

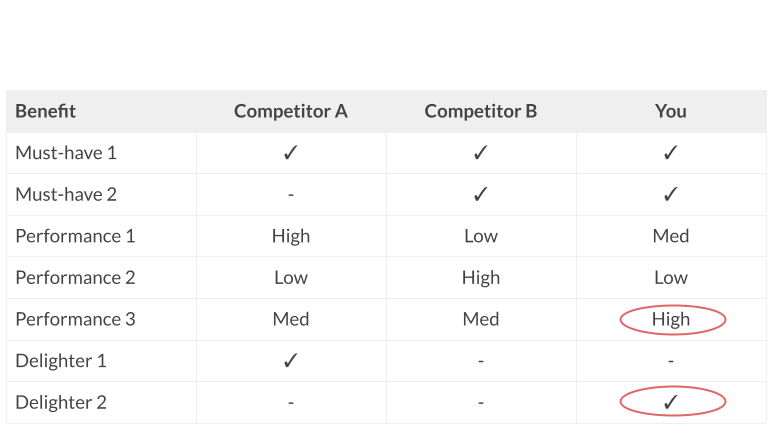

Using the Kano model on the level of benefits of the product, Dan Olsen creates what he calls a product strategy grid to compare your position to your main competitors.

The main take-away here is not that you need to be better at everything, but that you need to pick on which dimensions (benefits) you want to be the best! The unique combination of the performance benefits where you are the best and the delighters you offer is what sets you apart from all the competitors in the space. It’s the answer to the “why users should pick us?” question.

Let’s take stock of what we have so far: we know the market, the job we solve for the user, how our product does it, how we reach our users, how we make money and how we position ourselves against our competitors. That is starting to sound like a plan!

One thing is missing for us to talk about Priorities: which type of problem are we going to focus on in this phase? You have limited resources. You must make a choice.

Priorities

Within the Plan‘s frame of reference we can decide on how to best sequence the bets to reduce risk, increase optionality and focus. These (macro) Priorities sort the opportunities we have and help us decide which ones to tackle in the next cycles (1-4 quarters).

Things are getting more concrete here. Watch out to keep providing context and guidance, not dictate solutions (it’s a trap!). These questions and frameworks can help maintain the right level of abstraction and prioritise your opportunities:

What type of work are we focused on?

There is not only one type of product work (post-PMF). Product leadership and each product team need to be clear about which type of product work the organisation and each team is expected to do. Fareed Mosavat & Casey Winters describe these four types of product work:

- Feature Work – extending a product’s functionality

- Growth Work – accelerating adoption and usage by the existing market

- Scaling Work – ensure the team can continue to move forward and take on new levels of feature, growth, and product-market fit expansion work.

- Product-Market Fit Expansion – expanding into an adjacent market, adjacent product, or both.

Each of these types require a different approach and success will be measured differently. Even more importantly, not all of these types of work make sense in every stage of the company. Doing scaling or growth work for a product that actually needs feature work done is premature optimisation – and bad strategy.

Defining the type of work that is important in the next cycles is where the rubber meets the proverbial road. All the thinking of the Plan now gets concrete manifestations in form of work-packets. If the type of work is misguided, a lot of wasted work will be the result.

What opportunities are there that support our focus and further the Plan?

Based on the Plan and type of work we want to focus on, we can understand which opportunities we have insights on that make them worthwhile pursuing.

For example, given a growth focus and insights from data analysis that users of a particular segment have a higher LTV, we could decide to work on increasing LTV for other segments by looking at how the experiences across segments are different.

Or, given a feature strategy focus and armed with the insights from customer feedback through our off-boarding survey that our product is missing a feature users value in our competition’s product, we can decide to reduce churn and investigate the problem this competitor feature solves. (Note: I am not suggesting you copy features blindly. It could well be that your product “just” has a discoverability or usability problem here – the insight leads to the opportunity, not to the solution)

Due to the fact that product managers and product teams have more in-depth knowledge in their respective areas, they are encouraged to pitch opportunities they see (as long as they fit in the Plan and type of work).

| Opportunity template – What are we trying to achieve? (descriptive) – Why is this important? (connection to Plan) – Based on which insight? (how we know) – For whom is this? (target audience) |

How much time, money and resources are we willing to invest in each opportunity?

The product leader’s job is to weave strategic insights, learnings from teams and the market into a coherent story that supports the Plan, and to decide which opportunities get funding in the next cycle.

I like to think of all the possible opportunities as bets. Which ones are you going to bet on? And how much are you betting on each?

In ShapeUp the concept of “appetite” is introduced. It is a way to use time strategically by defining upfront how much time will be available to dwell on an opportunity, problem or project. It is much more reliable to limit time available than to “guesstimate” how much work would be needed to achieve a result. The time limitation acts as a forcing function. Yet another constraint that imbues the team with creativity.

This way of using time as resource also ensures that solutions (the “what”) and scope (the “how”) are the responsibility of the teams working on the problem. This is important, because we want the business outcome (seize the opportunity), but believing that our first idea will be the winner is delusional.

The team naturally starts off with some imagined tasks—the ones they assume they’re going to have to do just by thinking about the problem. Then, as they get their hands dirty, they discover all kinds of other things that we didn’t know in advance. These unexpected details make up the true bulk of the project and sometimes present the hardest challenges.

https://basecamp.com/shapeup/3.1-chapter-10#imagined-vs-discovered-tasks

Wrap it and keep at it

After going through this exercise you should have a sorted list of opportunities and will need to assign them as objectives to the teams. Each and every opportunity will be in line with your Perspective, support your Plan and be specific enough that a team can work on it, but not dictate the solution. The teams will know how much time they shall spend on which opportunity and which insight led to the opportunity being prioritised.

This is not a one-time exercise. This is an ongoing learning process. New insights will lead to new opportunities or even revise parts of the Plan. Learning about new user behaviour might even lead to a change in Perspective and which possible future you bet on. Nevertheless, at any point in time – as a product leader – you will be able to say exactly why the company is doing what it is doing. People can argue with the reasoning within the frame instead of throwing silver bullets at you. You can improve with their feedback or defend the decisions with the vast amount of thinking that went into them.

Last, but not least – the entire thing is meant as a thinking tool and the artefacts will help you communicate the context to the teams. Communicating the Perspective, Plan and Priorities is as important as creating them. You cannot over-communicate this. Remember to also communicate the new learnings you have along the way and incorporate the achievements into the bigger picture.

| Product Vision and Product Strategy You may be asking why I don’t call it “product vision” and “product strategy” in the first place. I feel that the terms are overused, misused and misunderstood. By overused I mean that everything that needs to be important is called “strategic”. Even if it has nothing to do with strategy, attaching the s-word makes it sound grand, high-priority. By misused I am referring to the vision, mission, strategy definition by some templates – often introduced by some consultant – and the very frequent confusion of vision/mission. By misunderstood I mean that people think strategy is static. Like a blueprint for the business on which we just need to execute. Strategy is fluid, because change is a fact in our world and markets. Incorporating new insights from the ongoing learning process is necessary. Strategy is a tool for alignment, it gives a frame of reference for decisions. It sets expectations. Nevertheless, if you ask me to map the 3P to product vision and product strategy, then this is what it would be: Perspective = product vision Plan and Priorities = product strategy |

tl;dr

Teams with direction and constraints innovate their way to success. We achieve this by giving Perspective, a Plan and setting Priorities. This reduces ambiguity and offers a surface to challenge/improve on. Don’t shy away from the work, it is one of the biggest levers you have as a product leader.